Santa Maria in Cosmedin

| Basilica of Saint Mary in Cosmedin | |

|---|---|

Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin (Italian)

Santa Maria de Schola Graeca (Latin) | |

Restored medieval façade of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, with original bell tower. | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 41°53′17″N 12°28′54″E / 41.88806°N 12.48167°E | |

| Location | Piazza della Bocca della Verità 18, Rome |

| Country | Italy |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Sui iuris church | Melkite Greek Catholic Church |

| Website | https://cosmedin.org/ |

| History | |

| Status | Minor basilica, titular church national church |

| Dedication | Mary, mother of Jesus |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | c. 550 |

| Completed | 1123 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 40 metres (130 ft) |

| Width | 20 metres (66 ft) |

| Nave width | 10 metres (33 ft) |

| Clergy | |

| Cardinal protector | Vacant |

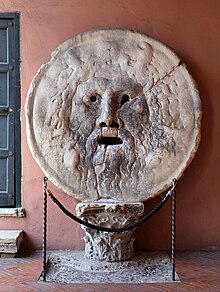

The Basilica of Saint Mary in Cosmedin (Italian: Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin; Latin: Santa Maria de Schola Graeca) is a minor basilican church in Rome, Italy, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It is located in the rione (neighborhood) of Ripa. Constructed first in the sixth century as a diaconia (deaconry) in an area of the city populated by Greek immigrants, it celebrated Eastern rites and currently serves the Melkite Greek Catholic community of Rome. The church was expanded in the eighth century and renovated in the twelfth century, when a campanile (bell tower) was added. A Baroque facade and interior refurbishment of 1718 were removed in 1894–1899; the exterior was restored to twelfth-century form, while the architecture of the interior recalls the eighth century with twelfth-century furnishings. The narthex of the church contains the famous Bocca della Verità sculpture.

Early history

[edit]The site

[edit]

The basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin is in an area of Rome along the Tiber River that once housed the Forum Boarium, the ancient cattle market, and a complex of temples and shrines to Hercules. Archaeologists discovered a platform of ancient tufa under the crypt of the church, which they have tentatively identified as part of the Great Altar of Unconquered Hercules (Latin: Herculis Invicti Ara Maxima), possibly dating from the sixth century BCE.[1] A later building on the site had a colonnaded loggia, probably constructed in the fourth century CE. This is thought by some to have been a statio annone, one of the government-run food distribution centers of ancient Rome,[2] but other scholars believe it was one of the buildings dedicated to Hercules.[3]

In the sixth and early seventh centuries CE, this area of Rome developed into a Greek quarter (schola graeca), a compound initially populated by Greek, Syrian, and Egyptian merchants and by functionaries of the imperial government in Constantinople during the Byzantine Papacy of 537–752, when the popes were approved by and subject to the Byzantine emperors. Several waves of eastern refugees added to the population as they fled from wars and persecution, the encroachment of Islam, and the violence of the Iconoclastic Controversy in the Christian East. The quarter became an important economic sector of the city and was allowed to govern itself with little interference from Roman authorities.[4]

The diaconia

[edit]Around 550, a hall was built on the site, incorporating some of the loggia columns of the previous building in its west and north walls.[5] This was identified as a diaconia (deaconry), an early Christian welfare center, where charitable distributions were given to the poor.[6] The brick masonry of the building was not typical of Rome at this time but was common in Naples in the sixth century, suggesting the work was done by Greek or South Italian builders, perhaps immigrants residing in the schola graeca. The hall itself was probably a gathering place and place of worship; two-story aisles on each side contained chambers on the ground floors, perhaps for the functions of the diaconia, and galleries above with six windows on each side, opening onto the main hall.[7]

Diaconiae were funded by wealthy individuals. A mid-eighth century inscription displayed in the narthex records a gift of extensive properties to the church's ministry to the poor by Eustathius (or Eustachius), a Byzantine duke of Rome who had administered the territory of Ravenna for the papacy.[8] The same inscription also mentions a donation by a “vir gloriossimus [most noble] Georgios” and his brother, David.[9]

The eighth-century church

[edit]Pope Hadrian I (papacy 772–95) rebuilt and extended the diaconia around 780, demolishing a large ruined temple to make way for this construction.[10] The result was a basilica dedicated to the Virgin Mary, at that time called Santa Maria de Schola Graeca or the ecclesia graecorum (Greek church) because of its location and a community of Greek monks there.

The church was built with a nave and two aisles, but it culminated at the east end with three full apses, an eastern feature unusual for a Roman church, but one that had reached the West by the sixth century.[11] In the rebuilding, the tall columns from the structure that preceded the diaconia were retained and were visible (and still are) in the entrance wall and embedded in the side walls at the western end of the church.[12] In the center apse was an altar made from a Roman red granite basin, and the floor was a simple opus sectile pattern.[13] The nave was separated from the aisles by alternating groups of columns and piers; the unmatched columns were spolia (spoils) from older Roman buildings. Some scholars believe that the columns supported a trabeation (lintel) at this time and not arches.[14] On the upper level of the outer walls, rows of clerestory windows repeated the motif of the arches in the diaconia that had opened into galleries.[15] By the ninth century, the church was known as Santa Maria in Cosmedin, probably the Latinization of κοσμίδιον (kosmidion), derived from the Greek word κόσμος, meaning "ornament, decoration."[16]

At the same time, Pope Hadrian had a crypt dug from the volcanic tufa slab under the east end of the church, possibly the podium of the Great Altar to Hercules.[17] It took the form of a miniature basilica with a small apse and altar and a nave and two aisles separated by columns, probably based on a prototype under Old Saint Peter’s Basilica.[18] The six spolia columns were too tall for the crypt and had to be sunk several feet into the floor. Carved crosses on the columns may have been inset with bronze.[19] On the side walls were niches containing shelves for the display of relics given by Pope Hadrian to the church.[20]

A sacristy and an oratory later dedicated to St. Nicholas of Bari, as well as a series of rooms for a papal residence, were added on the south side of the church by Pope Nicholas I (papacy 858–67).[21][22] This area was burned in the sack of Rome by the Norman troops of Robert Guiscard in 1084.[23]

The twelfth-century renovation

[edit]In the early twelfth century, Pope Gelasius II (papacy 1118–19), who had served as cardinal-deacon of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, and his successor, Pope Callixtus II (papacy 1119–24), undertook a renovation of the church, probably in 1120–23.[24] Although the plan remained the same, many changes were carried out: the galleries at the west end, remaining from the diaconia, were walled up, frescoes were painted in the nave and apses, a new floor was laid in the nave, and many new church furnishings were added, including a ciborium, bishop's throne, Paschal candlestick, and a schola cantorum, a walled enclosure at the front of the nave for clergy and monks, containing the pulpit and lectern. At this time, the trabeation supposed by some scholars to have carried by the columns in the nave would have been changed to arches. A campanile was then built into the right side of the church and, finally, a two-story narthex (the lower floor was open to the street) and a portico were added.[25]

Callixtus II reconsecrated the church in May of 1123. A number of inscriptions state that the renovations were paid for by Alfanus, a wealthy layman or cleric who served as papal chamberlain (Latin: camerarius) to Callixtus. On the bishop's throne is carved "ALFANUS FIER TIBI FECIT VIRGO MARIA" (Alfanus had this made for you, Virgin Mary). The open narthex of the renovated church contains the tomb of Alfanus, partly decorated with a damaged mosaic depicting the Virgin Mary between Popes Gelasius II and Callixtus II. On the walls are several panels of inscriptions recording monetary gifts to the church.[26] The inscriptions found in Santa Maria in Cosmedin, a valuable source for the history of the Basilica, have been collected and published by Vincenzo Forcella.[27]

There are three doors leading from the new narthex into the church. The center door is created of marble elements from older Roman buildings, with medieval carvings signed by a "Giovanni of Venice" (IOHANNIS DE VENETIA ME FECIT). Scholars differ on whether it is from the eleventh or twelfth century, so it is possible this was the door to the church before the narthex was added.[28]

The nave floor in the renovated church was a creation of the Cosmati family, Roman architects, sculptors, and decorators, who specialized in pavements formed of slabs of marble and semi-precious stones set in gold and colored mosaics, called opus Alexandrinum. Santa Maria in Cosmedin is thought to have a particularly beautiful floor with a large central disc of porphyry, a costly purple stone highly prized by Roman emperors. The Cosmati also provided and decorated the bishop's throne and the pulpits and candlestick inside the schola cantorum.[29] The current ciborium, the canopy over the altar, was designed by Deodato of the Cosmati; it was installed in 1294 and is in a Gothic style not common in Rome.[30]

At the time of Pope Callixtus's renovation, an extensive fresco cycle was painted on the nave walls and the arch leading to the altar area; the decoration probably extended to the three apses as well, but no traces remain in those areas. All the paintings were whitewashed about 1649–60 and were badly damaged. Only the uppermost row between the clerestory windows survives intact and depicts scenes from the lives of the prophets Daniel and Ezekiel, warning against the evils of idolatry; the subjects are very unusual in medieval art. The images are faint but were photographed and sketched during the nineteenth-century restoration. There are enough fragments to suggest that there were scenes from the New Testament on two lower rows of the nave wall[31] and that the scene over the arch into the central apse showed Jesus enthroned amid a host of angels.[32] Running along the very top of the nave wall is an undated frieze in which are painted fauns' heads and other ornaments in ancient Roman style.[33] The frescoes now in the three apses were painted in 1899 but based on styles and themes of twelfth-century church decoration.[34]

The campanile of Santa Maria in Cosmedin is a beautiful seven-story bell tower that has stood without repair or restoration since its twelfth-century construction. Drawings and engravings from later centuries show a superstructure above and behind the portico and narthex of the church, consisting of a wall with a small rose window.[35]

Later history and restoration

[edit]

Pope Eugenius IV (papacy 1431–47) gave Santa Maria in Cosmedin in 1435 to the Benedictine community of San Paolo; after the monks' departure in 1513, the church began to fall into disrepair.[36] In 1718, Cardinal Annibale Albani commissioned a new stucco facade and other refurbishments designed in the late Baroque style of the time by Giuseppe Sardi.[37] This facade and all of the post-medieval changes to the church inside and out were removed in a restoration of 1894–99 by architect Giovanni Battista Giovenale.[38] The facade was returned to its early twelfth-century form, with a rebuilt portico and open narthex, and the interior was restored to its eighth-century design but with the retention of its twelfth-century decoration and furnishings.[39] Only two sections of the interior - the Chapel of the Crucifix in the left apse and the baptistery - retain some furnishings from 1727.[40]

Santa Maria in Cosmedin was the titular church not only of Pope Gelasius II but also of Celestine III (papacy 1191–98) and antipope Benedict XIII (papacy 1394–1423). Among the former cardinal-priests of the church was Reginald Pole (1500–1558), the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury.[41]

Within the church

[edit]

In the open narthex of the church, on the north side, can be found the Bocca della Verità (Mouth of Truth), a massive ancient Roman marble mask thought to be a drain covering depicting the Greco-Roman god Oceanus; it was moved to the church in the twelfth century. A medieval legend states that if a person places a hand inside the mouth ("bocca") and then swears falsely, the mouth will close and sever the hand.[42]

The sacristy houses an important mosaic fragment of an Adoration of the Magi from 706–07. It was once in the oratory of Pope John VII in Old Saint Peter's Basilica[43] and was donated to the church in 1639 by order of Pope Urban VIII.[44]

Among the relics of several dozen saints in Santa Maria in Cosmedin, in a side altar on the north side is a flower-crowned skull alleged to be Saint Valentine, a third-century Roman cleric martyred on February 14. There are, however, two other Valentines with commemorations on that day, so the specific identity is not certain.[45]

In popular culture

[edit]A scene from the 1953 romantic comedy Roman Holiday was filmed in Santa Maria in Cosmedin. In the scene, Joe (played by Gregory Peck) shocks Princess Ann (played by Audrey Hepburn) by pretending to lose his hand in the Bocca della Verità.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Filippo Coarelli, Il foro boario dalle origini alla fine della repubblica (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 1992), vol. 2, 61–77.

- ^ Andrew J. Ekonomou, Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern Influences on Rome and the Papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007), 209; Richard Krautheimer, Rome: Profile of a City, 312–1308 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 35.

- ^ Filippo Coarelli, Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide, James J. Clauss and Daniel P. Harmon, trans., rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), n.p.

- ^ Krautheimer 1980, 60, 75–76, 89–90.

- ^ Maria Fabricius Hansen, The Spolia Churches of Rome: Recycling Antiquity in the Middle Ages, Barbara J. Haveland, trans. (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2015), 64, 168.

- ^ Thomas F. X. Noble, The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal States, 680–825 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984), 231–33.

- ^ Krautheimer 1980, 78.

- ^ Noble 1984, 105, 250.

- ^ Ekonomou 2007, 64n.5.

- ^ Richard Krautheimer, Wolfgang Frankl, and Spencer Corbett, Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae: The Early Christian Basilicas of Rome, IV to IX Cent. (Vatican City: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1959), vol. 2, 279.

- ^ Krautheimer, Frankl, and Corbett 1959, 306; Krautheimer 1980, 105.

- ^ Hansen 2015, 168–70.

- ^ Guida d'Italia: Roma e dintorni, 6th ed. (Milan: Touring Club Italiano, 1965), 409.

- ^ Krautheimer, Frankl, and Corbett 1959, 296, 302.

- ^ Krautheimer 1980, 105.

- ^ Ekonomou 2007, 42.

- ^ Hansen 2015, 172.

- ^ Charles B. McClendon, The Origins of Medieval Architecture: Building in Europe, A.D. 600–900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 175.

- ^ Hansen 2015, 172–73.

- ^ McClendon 2005, 176.

- ^ Krautheimer, Frankl, and Corbett 1959, 279–80.

- ^ Giovanni Battista Giovenale, La Basilica di S. Maria in Cosmedin (Rome: Sansaini, 1927), 279, fig. 87.

- ^ Daniela Gallavotti Cavallero, ed., Rione XII – Ripa – Parte II (Rome: Fratelli Palombi, 1978), 94.

- ^ Kenneth John Conant, Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture, 800–1200, The Pelican History of Art, 2nd ed. rev. (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1978), 372.

- ^ Krautheimer, Frankl, and Corbett 1959, 302.

- ^ Anne Derbes, "Crusading Ideology and the Frescoes of S. Maria in Cosmedin," Art Bulletin 77 no.3 (September 1995): 462.

- ^ Vincenzo Forcella, Inscrizioni delle chiese e d'altre edifici di Roma, dal secolo XI fino al secolo XVI (Rome: Fratelli Bencini, 1874), vol. 4, 301–27.

- ^ Hansen 2015, 165, 168.

- ^ Conant 1978, 368.

- ^ Guida d'Italia: Roma e dintorni 1965, 409.

- ^ Derbes 1995, 461, 463.

- ^ Matilda Webb, The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome: A Comprehensive Guide (Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2001), 177.

- ^ Krautheimer 1980, 186.

- ^ Guida d'Italia: Roma e dintorni 1965, 409.

- ^ Krautheimer, Frankl, and Corbett 1959, 303.

- ^ Mariano Armellini, Le chiese di Roma dal secolo IV al XIX (Rome: Tipografia Vaticana, 1891), n.p.

- ^ Nina A. Mallory, "The Architecture of Giuseppe Sardi and the Attribution of the Facade of the Church of the Maddalena,' Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 26, no. 2 (May 1967): 83–87.

- ^ Giovenale 1927.

- ^ Krautheimer, Frankl, and Corbett 1959, 281–82.

- ^ Varisco, Alessio (2008). "La Basilica Santa Maria in Cosmedin". antropologiaartesacra. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Frederick George Lee, Reginald Pole, Cardinal Archbishop of Canterbury: An Historical Sketch, with an Introductory Prologue and Practical Epilogue (London: J. C. Nimmo, 1888), 21.

- ^ Fabio Barry, "The Mouth of Truth and the Forum Boarium: Oceanus, Hercules, and Hadrian," Art Bulletin 93, no. 1 (March 2011): 7–37.

- ^ Roma e dintorni 1965, 409.

- ^ Webb 2001, 177.

- ^ Agostino S. Amore, "S. Valentino di Roma o di Terni?" Antonianum 41 (1966): 260–77.

Bibliography

[edit]- Coarelli, Filippo. Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. Translated by James J. Clauss and Daniel P. Harmon. Rev. ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

- Crescimbeni, Giovanni Mario. Stato della basilica diaconale, collegiate, e parrocchiale di S. Maria in Cosmedin di Roma. Rome: Antonio de' Rossi, 1719.

- Fusciello, Gemma. Santa Maria in Cosmedin a Roma. Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2011.

- Giovenale, Giovanni Battista. La Basilica di S. Maria in Cosmedin. Monografie sulle chiese di Roma 2. Rome: Sansaini, 1927.

- Glass, Dorothy F. Studies on Cosmatesque Pavements. Oxford: BAR, 1980.

- Hansen, Maria Fabricius. The Spolia Churches of Rome: Recycling Antiquity in the Middle Ages. Translated by Barara J. Haveland. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2015.

- Krautheimer, Richard. Rome: Profile of a City, 312–1308. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980.

- Krautheimer, Richard, Wolfgang Frankl, and Spencer Corbett. Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae: The Early Christian Basilicas of Rome, IV to IX Cent. Vol. 2. Vatican City: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1959.

- Varisco, Alessio. "La Basilica Santa Maria in Cosmedin. antropologiaartesacra 2008. http://www.antropologiaartesacra.it/ALESSIO_VARISCO_ROMASantaMariaInCosmedin.html#_ftnref1.

External links

[edit] Media related to Santa Maria in Cosmedin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Santa Maria in Cosmedin at Wikimedia Commons- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Santa Maria in Cosmedin | Art Atlas

| Preceded by Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria in Montesanto |

Landmarks of Rome Santa Maria in Cosmedin |

Succeeded by Santa Maria in Domnica |